Stanley Everard STEPHENS

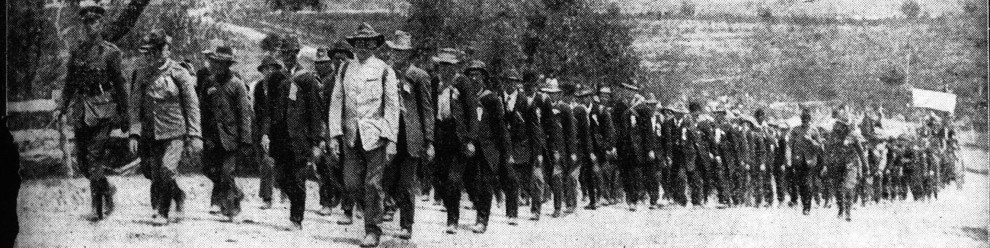

Stanley Everard Stephens (Photograph courtesy of M. Stephens)

Per his military service record (regimental no. 6320), Stanley Everard Stephens was born at Melbourne, Victoria. He gave his age as 24 years and 11 months, his marital status as single, and his occupation as journalist. His description on his medical was height 5 feet 7 inches tall, weight 136 lbs., with a fair complexion, brown eyes, and brown hair. His religious denomination was Church of England. He claimed to have previous military service with the Naval Reserve and the New Guinea Expeditionary Force. He completed his medical on the 9th October 1915 at Gilgandra (the day before the commencement of the Coo-ee March), and was attested by Captain Nicholas at Gilgandra on the 9th October 1915.

Stanley Stephens joined the Coo-ee March as both a recruit, and as a special reporter to The Farmer and Settler, of which his father Harry J. Stephens was the editor.

On the march he was given the rank of Acting Sergeant, and was appointed Secretary of the travelling committee of control appointed for the Coo-ee March at Stuart Town, with Major Wynne as chairman, Captain Hitchen, Q.M.S. Lee, and Mr H. T. Blacket, during a visit by A. H. Miller (Secretary), and C. H. Richards and P. J. MacManus, from the Gilgandra Recruiting Committee.[1] In this role he assisted with the day to day running of the march, and maintained the accounts.[2]

After completing the march he went to Liverpool Camp as reinforcement for the 13th Battalion. He was made Acting Company Sergeant Major on 16th November 2015.

On 7th February 1916 Acting Company Sergeant Major Stephens was sent to the Depot School for NCO’s, then on 18th March 1916 he was sent to the Officer School at Duntroon.

His father Harry Stephens wrote in a letter to A. H. Miller (Secretary of the Gilgandra Recruiting Committee) dated 9th March 1916 (the day after most of the Coo-ees embarked for Egypt on the HMAT A15 Star of England) : ‘Stan is now at the officers’ school, which this week is at the show ground, Sydney, but next week should be at Duntroon. The Coo-ees sailed on Wednesday morning. They spent the previous night at the show ground and Stan was with them right through and saw them off. He would have liked to go with them, but I thought he ought not to miss the greater opportunity offered in the officers’ school. He speaks of them as the finest of all the reinforcements that were reviewed the other afternoon. They have done well so far, and there need be no doubt of the record they will put up when they join the 13th. in Egypt – one of the battalions that has done excellently in the Gallipoli fighting.’[3]

He returned to the 13th Battalion on the 10th of May 1916 as Acting Company Sergeant Major.

On his embarkation roll his rank was Acting Sergeant, and his address at time of enrolment was 25 Roslyn Gardens, Darlinghurst, N.S.W., and his next of kin is listed as his mother, Mrs E. [Effie] Stephens, 19 Roslyn Gardens, Darlinghurst, N.S.W.

Acting Sergeant Stephens departed Sydney on the HMAT A14 Euripides on 9th September 1916 as 20th reinforcement for the 13th Battalion, and arrived in Plymouth, England, on 26th October 1916. With him travelled fellow Coo-ees Acting Sergeant Thomas W. Dowd, and Acting Corporal Francis Charles Finlayson.

On 4rd November 1916 Acting Sergeant Stephens marched into the 4th Training Battalion at Codford, England.

On 20th December 1916 Acting Sergeant Stephens departed Folkestone aboard the SS Princess Clementine bound for France. On 22nd December 1916 he arrived at the 4th Australian Division Base Depot at Etaples, France, where he reverted to the rank of Private.

The Farmer and Settler reported that ‘Stan E. Stephens, of the “Farmer and Settler” staff, who left Sydney as sergeant-major of a reinforcement company of the 13th Battalion, lost his n.c.o. rank as soon as he set foot in France, because the Australian army there has a healthy regulation that gives precedence to men that have earned their stripes’.[4]

On 2nd January 1917 Private Stephens joined at the 13th Battalion at Ribemont, France, to undergo training.

Private Stephens described his first “baptism of fire” going “over the top” on a raid on a German trench in the front line in the vicinity of Guedecourt, France, on the night of 4th February 1917, in a letter home that was published in The Farmer and Settler on 17th August 1917.[5] He wrote:

… “Some one said: ‘Get ready’, and I was just wishing I was at home, or anywhere else in the wide world, when a fervent ‘Ah!’ in the vicinity made me look around. A mess-tin full of rum was being passed along. Everyone took a swig, and passed it on. There was plenty in it when it came to me, and I just gulped down a couple of mouthfuls and handed it to Fin [Finlayson], when, ‘bang,’ ‘bang,’ ‘screech,’ ‘screech,’ over our heads came some shells. Many men involuntarily ‘ducked,’ but were reassured by someone saying: ‘They’re ours.’ So they were. The barrage had started — only a minute to go! Thank Heaven for that rum. It pulled me together, stopped the nervous trembling that made me afraid that everybody would notice me and think I was going to ‘squib’ it. I was cool enough to notice things then, but still I glanced hatefully now and then at the top of the bank above me.

“Somebody said: ‘Now!’ There was a bustle, and I found myself up in No Man’s Land jostling someone to get around a shell-hole. The order had come simultaneously from both ends of our line, so that we at the centre were a bit behind — a sag in the middle. Everything could be seen as clear as day; the line stretched out to right and left. We crouched in our advance, moving slowly, picking our way, with the shells shrieking over us, and bursting only a few yards in front of us. I thought about the ‘backwash.’ Why weren’t some of us killed. Would they knock our heads off if we stood up straight? We were in semi-open order, perhaps five or six deep, and advancing slowly. Oh!, the weight on my back from the heavy kit and the stooping. Yet I felt amused at the struggles of a chap that was sitting down, softly cursing a piece of barbed wire— such silly, meaningless curses. Another stumbled in front of me, and I nearly jabbed him with my bayonet. Then I looked around smartly, to see if any one was close enough behind me to treat me likewise.

“The wire! We were up to it already. But the shells weren’t finished. They had made a good mess of it, I saw as I stepped through from loop to loop. A piece caught me somewhere, but something gave way and I was free again. No; the shells weren’t finished yet. ‘They are bursting behind me.’ I exclaimed to myself, ‘Why on earth don’t I get killed? Are they charmed, so as to kill only Fritzes.’ I caught the flash of another out of the tail of my eye, and then there was a straight line of intermittent flashes in front. What’s this? At that moment I slid and scrambled down a steep, bank and found myself in the German trench!

“Our barrage was just lifting. A Fritz officer afterwards said: ‘I knew you were Australians; you come in with your barrage; you are too quick for us.’ Yes, we went in with the barrage, instead of a few moments after it— and without a casualty!

“The details of this, my first hop-over, my baptism of fire, are indelibly printed on my memory. I shall always remember the impressions made on me, down to the most trivial incident of the hop-over. Thinking over it afterwards, I have tried to reason out why we got in with our barrage. It’s a good fault, for it prevents the Germans from getting ready for us when the barrage lifts. The Germans reckon that the Australians are always too quick for them that way. I certainly believe that a spirit of ‘don’t-care-a-damn’ was abroad; or, maybe, it was hereditary bloodthirstiness that came out in the excitement, and made us, for the time being, all ‘hogs for stoush.’ I think only the fear that we would be killed by our own curtain of fire kept us from actually running. It wasn’t the rum, anyhow, as the slanderous have asserted. The rum, I found out afterwards, was our first casualty, being broken in the coming up, so that the only rum issued was half a demi-john to a small section of trench that I happened to be in. The jar was found by a chap taking German prisoners back half an hour later, still nearly half full.’… [Click here to read a full transcription of this article: https://cooeemarch1915.com/2015/03/19/stanley-e-stephens-letter-about-his-baptism-of-fire-in-the-trenches]

Three days later, on 7th February 1917 Private Stephens was slightly wounded in action whilst the Battalion was in action near Guedecourt, France. He was one of 51 wounded this day another 21 members of the Battalion were killed. He re-joined the Battalion on 15th February 1917 whilst it was training and conducting fatigues at Mametz, France.

Just over two months later, on 11th April 1917 Private Stephens was reported Missing in Action during an attack on the Hindenburg Line near Bullecourt, France. He was one of 367 men from the Battalion reported missing this day, and another 25 were killed and 118 wounded.

After a Court of Enquiry was held by the Battalion on 8th October 1917 Private Stephens was officially listed as Killed in Action.

Private Stephens has no known grave, and his name is commemorated on the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, France.

Private Stephens’ name on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial, France (Photograph: S. & H. Thompson 7/9/2014)

Private Stephens’ name is also commemorated on panel 71 on the Australian War Memorial First World War Roll of Honour.

[1] ‘Our soldiers’, The Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate, 26 October 1915, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article77601552

[2] ‘Gilgandra Recruiting Association’, Gilgandra Weekly, 10 December 1915, p. 6, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article119922432

[3] Letter from H. J. Stephens to A. H. Miller dated 9th March 1915 in: Alex Halden (Joe) Miller papers mainly relating to the Gilgandra Coo-ee Recruitment March, New South Wales, 1912-1921, 1939. Gilgandra Coo-ee Recruitment March correspondence and papers, 1915-1939.

[4] ‘The soldiers that voted “No”’, The Farmer and Settler, April 1917, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116643546

[5] ‘A baptism of fire’, The Farmer and Settler, 17 August, 1917, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116642518