Letter from W. H. Saunders about his voyage on HMAT A15 Star of England ,and arrival in Egypt, 1916

Most of the Coo-ees were transported from Sydney to Egypt on the troopship HMAT A15 Star of England, which embarked from Sydney on the 8th March 1916. A photograph of the ship from an earlier voyage is pictured below.

Details about this voyage were included in a letter William Hilton Saunders (a Coo-ee from Wongarbon) wrote to his parents, which has been transcribed below. The undated letter was published in an article titled ‘Australians in Action. Letters from the Front’ in the Wellington Times, 29 June 1916, p. 3.

Troopship, HMAT A15 Star of England at the docks, 1914 [on an earlier voyage]. Photo courtesy of: John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Image number: APE-039-01-0009

‘Australians in Action.

Letters from the Front.

… Driver Hilton Saunders, son of Mr. and Mrs. E. J. Saunders, of Wongarbon, writes as follows to his parents:—

I am still O.K., and still enjoying the happy-go-lucky life of an Australian soldier. I have now settled down to camp life after having had a most enjoyable trip over the water from Sydney. There is no doubt it was a lovely trip from the very day we left Sydney till we landed in Port Said. I will try and give you a brief description of some of some of our experiences and the sight we saw.

To begin with I will give you an idea of how calm the sea is in the tropics at times. Well at times it has the appearance of a very calm lake with not even a ripple on the surface except those made by the troopship. I was simply entranced when I first noticed it, and I began to imagine I was once again out on one of the Great Western Plains with a mirage dancing before my eyes; for such it resembled. You have not the slightest idea of what it looks like. The whole spectacle was a revelation to me, because I did not think the restless ocean could be so calm and placid. Then towards evening one sees more grandeur presented by nature in the form of sunset. One sunset in particular presented a very fine spectacle. Viewed from the troopship it looked like a vast work of art featuring an undulating landscape dotted with spreading trees, vegetation, lakes, and rivers. At first the whole scene was of a greyish tinge, but gradually changed to a reddish glow; giving the appearance of a bush fire raging amongst the timber in its midst. Certainly one of the most picturesque sights that has come my way since leaving Sydney. Well, mother dear, I will not weary you with descriptions of tropical sunsets, etc., but will tell you a few of the happenings on the way to Ceylon. Well, after leaving Sydney, we hugged the coast for a few days, and then lost sight of land till we hit the West Australian coast, somewhere about Cape Leeuwin. We only got a glimpse of the hazy coast line, and many were the speculations regarding our chances of landing at Fremantle. However, we were doomed to disappointment, for when we looked out next morning (Thursday 16th), all that met our gaze was an endless waste of water. Nothing very eventful happened on the way to Colombo, not even when crossing the “line” because the Colonel, for certain reasons, would not allow any celebrations to take place. On Saturday, 25th, at about 8 a.m., we sighted the coast of Ceylon. Everyone was happy and excited, because it meant, to most of us, our first glimpse of foreign land. We hugged the coast all day and dropped anchor inside the breakwater at sundown. All along the coast are to be seen hundreds of natives out in their little boats catching fish. These boats are very comical little structures cut out of a log of wood. They are about as long as one of our rowing boats at home, and just wide enough for the natives to sit in, which means about 14 or 15 inches. They have another piece of wood the same length as the boat itself, and this is lashed to the side with two pieces of bamboo and some rope. They are said to be very safe even in very heavy weather. Nearly all of them carry from two to eleven natives. Colombo has not a natural harbour, so three breakwaters had to be built at a total expenditure of £1,000, 000, and no doubt it is a wonderful piece of engineering. We were hardly stationary before the native coolies were swarming round the boat on barges loaded with coal. Of course, they don’t load coal in Columbo with the assistance of machinery the same as they do in Newcastle, but everything has to be done by black labor. These follows are a very dirty low-bred class of men, very small and thin, but very wiry. They bring 50 tons of coal in each barge, and it is all packed in bags, just the same as onion bags. The barges are brought up along-side the ship by a tug and made fast then after a lot of jabbering the loading begins. A kind of staging or scaffolding is rigged on the ship’s side in tiers, two men standing on each tier.

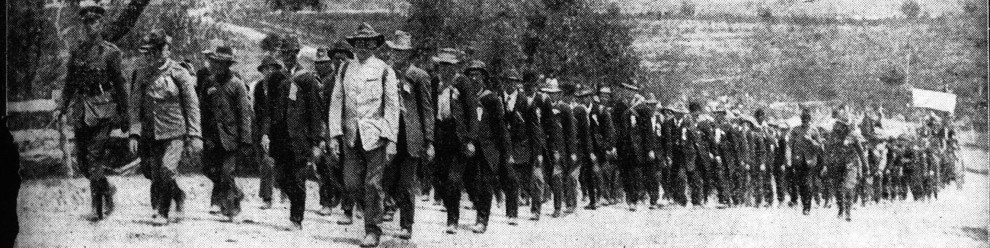

Each bag is lifted separately from the barge to the men on the lower stage, and so on till it reaches the deck, then two more men place it on the shoulders of a native, who carries it to the bunker hatch, and drops it in. Simple enough on paper, but in practice very hard work, and I, for one, would not care about taking it on for twenty times as much as the nigger gets (about 1s. per day). This coaling was carried on all day and all night for two nights and a day from either side of the ship, so you can guess what a state everything was in from coal dust. It seemed to penetrate everything on board, and we were continually washing ourselves, but were always dirty; in fact, it was with difficulty that our officers picked us out from the Cin- galese. On Sunday morning we all had an early breakfast, and half the boys went ashore in lighters towed by a tug at 7.30 a.m. The remainder including the Coo-ees, went off at 10 a.m., when the others came back. We were marched round the town through the main streets, and down past the military barracks along the promenade to the Grand Hotel. Then we turned round and marched back again to the barracks, were we broke off for about three-quarters of an hour, and were treated to cool drinks. We were not allowed to leave the grounds, but there were dozens of natives selling fruits, silks, postcards, curios, etc. Fruit is very cheap, and bananas can be bought about ten dozen on a bunch for 1s., cocoanuts and pineapples 1d. each. Needless to say we all speculated to a great extent in fruit, which was a welcome luxury to us after being so long without it. Nearly all the Ceylon goods are fairly cheap, but anything of English manufacture is dear. The natives have their own way of doing business, and deal very much the same as the Arabs of Egypt. They will ask 8s. for an article which can be bought after a little barnying for about 1s. 6d. Cigars can be bought in Columbo from ls. 6d. to 5s. per box of 50, and they are real good one’s too. Everybody has something to sell from the oldest man down to the smallest boy. They are also the greatest “hums” under the sun, and I think they are taught to beg before they are out of their cradles, and thieves is no name for them; why they would steal the milk out of your tea while you were looking on. Well, when we had had a rest and eaten nearly all the fruit about the town, we were marched back to the wharf and taken back to our ship (2.30 p.m.). Everybody was disappointed at not be-ing given a free hand to see the town, and a lot of them managed to get back to shore the same night in coal barges, although a strict watch was kept by officers, guards, and native harbour police. I myself was down in the middle of a dirty old coal barge once or twice, but was always shrewd enough to get caught and hunted back on the beat. Next morning I went for a swim alongside the troopship, and among others got very sunburnt on the shoulders and arms. After lunch Mac, Ernie, Will Collyer, and a lot more of us got down a rope (very much against the rules) on to a water barge which was just about to leave for the shore for another supply of water. Once on shore again we began to look about and enjoy ourselves. First of all we had a look around the Customs Offices and wharves; everything here is done by the natives; office work and every-thing. Then we made our way down to the markets, which are a series of shops ranging in size from a small room about 4 by 4 feet to larger and better kept places. The streets leading through the markets are only about 14 or 15 feet wide, and are lined from one end to the other with carts or drays drawn by oxen which are very different to the cattle of our climes; they are only about the size of an 18-months’ old steer, and have a small hump on the top of their shoulders, very much resembling a buffalo in miniature. They are capable of pulling a fairly large load, and if there is one of these oxen-drawn carts in Columbo, well there must be two or three hundred. Everything imaginable is sold in these markets, fruit, vegetables, nuts, flowers, curios, drinks, clothing, birds, monkeys, etc. We did not speculate in the wares because the shops are absolutely filthy in general; so filthy that we had to hold our noses while walking past some of the shops. Of course, there are some as fine shops as I have seen anywhere. One, for instance, Cargills, Ltd., which is situated on a corner just up about 100 yards from the wharf is just as up-to-date as Anthony Hordern’s, only, of course, it is not as big. Almost anything can be bought at Cargills, including all the goods and luxuries specially manufactured for the tropics. The labor employed is mostly white, and there are hundreds of large electric fans running all day to keep the building cool. Then there is the Bristol Hotel, which was built about 200 years ago by the Spaniards, and is a beautiful big building and very comfortable inside. There is also the Grand Hotel, which is situated about 60 yards from the beach, and overlooking the Indian ocean; no doubt a beautiful hotel, and equal in comforts and cuisine to any hotel in Sydney. After seeing a few more of the principal buildings such as the post office, Mosque, Town Hall, etc., we went to the railway station and saw a train go out. From there we went and had a ride in one of the electric trams, which are very much the same as our own with the exception that they are driven by niggers (instead of whites), who are dressed in a kind of light khaki uniform. Charlie Gardiner and I then hired a rickshaw each and went for a ride all over the town again. The day being very hot, my nag began to perspire very freely, but nothing daunted kept up his steady trot, and when he happened to slacken down a little I would break a banana off the bunch I had with me, and hit him in the middle of the back. Off he’d dart again as if stung by a hornet or some other equally venomous insect. To see these fellows trotting down the street they look for all the world like emus, and many were the memories recalled to mind of the Western Plains, when I saw them for the first time. Most of the niggers who pull a rickshaw are very fine indeed, and it is almost possible to hear your pal change his mind on the opposite side of one of them. On our arrival back at the wharf we were making preparations to go aboard when lo and behold! and much to our dismay, the Star of England was just clearing the breakwater. The niggers absolutely refused to take us outside the breakwater to her, so we did not know what to do. We could see the boat outside the harbour steaming slowly, but did not know whether she was going to wait for us, or go straight on, so after a bit of consultation among ourselves we came to the conclusion that she would not wait because a troopship before us had gone off leaving over a hundred men behind to be taken on by another steamer following in a few days. Damp were our spirits, but “ne use for to cry,” so we decided to make the best of a bad thing, and contented ourselves by eating bananas and dried-figs, and discussing the future. However, after going out about a mile our ship “hove to” and dropped anchor (much to our joy), and we were taken out to her in a pilot launch. Our names were taken, but nothing happened to any of our company, although a few of another company were carpeted and fined £5 or 28 days’ detention for breaking ship. After everything turned out alright I was, in a way, glad that we missed the boat, because it gave us a bit of a lesson in punctuality. We left Columbo about 1 a.m. on Tuesday, and passed Aden about lunch time on April 4th, but did not call. The sun was very hot on April 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th, just as we were entering the Red Sea. I think the passage is called “Hell’s Gates,” and it is well named. After passing well into the Red Sea the weather began to get very much cooler. On Sunday morning, the 9th, we arrived at Suez at about 5.30 a.m., and left the same afternoon at sundown for Port Said, where we arrived early on the morning of the 10th, on Dorrie’s birthday. We had the bad luck to go through the Suez Canal at night time, and, of course, could not see very much of the scenery if there is any, but I think all that is to be seen is sand, and, of course, the bitter lakes. As soon as we dropped anchor the niggers commenced coaling, but they work very differently to the Cingalese. The coal is brought to the ship’s side in barges, and two long planks are laid from the barge to the ship; the coal is shovelled into baskets which are just the same as a carpenter’s tool carrier, and then these baskets are carried up one plank on the shoulders of coolies, who tip the coal down into the bunker hatch, and race back as quickly as possible down the other plank for another load, which is already waiting for them. They are yelling the whole time this is going on, and it is hard to hear yourself speak where they are working. They remind one of black ants, as they rush backwards and forwards with their grimy loads, but they are great workers, and do twice as much work as the Cingalese. Port Said is said to be the fastest coaling port in the world, and I don’t doubt it the way these niggers work. We were taken ashore on Tuesday morning, and taken straight to camp at Tel-el-Kebir, where we were quartered for a week only. While there I met Corporal Jack Clements when he arrived from Australia, also met Jack Hives in the Light Horse Camp. He looks well, and seems quite contented. We had a long yarn. Since coming here I have met several Dubbo chaps. There is one chap in our tent named Arthur Kidby from ‘Wait-a-While,’ just out of Dubbo, also another chap who was out on Condon’s place when Mr. Condon first came to Wongarbon. He brought his horses over for him. Aubrey Field is also in the 46th battery. I saw Len Butcher here to-day. He brought some horses from Luna Park at Heliopolis to our battery. Roy Stanbridge, who used to be with Dick Skuthorpe, was with Len, and they both look well. Roy is breaking in horses and mules in the remount unit. A couple of days ago somo artillery chaps came here from Cairo, and amongst them was Arthur Roche, who after being wounded, was sent to England, where he has been for the last eight months, and only came back about three weeks ago. He is in one of the batteries, and wishes to be re-membered to Uncle J. Dunn, etc. On Sunday afternoon I walked into the coffee canteen, and who should be there but Alf. McLean, of Orange. He went down to Sydney with us, and afterwards joined the 1st A.L.H. He came over since we did, and was up here visiting his brother. I have not struck Roy Bowling or Uel Armstrong, Lou Lassers, or the Spencer boys yet, but I know where Lou and Norman Levett are, and may get a chance to see them later. They are about twelve miles from here, and Norman has a commission in the 54th battalion. Len Butcher says he saw Jim Olsen about five or six days ago in Cairo. Try and send me the full address of Roy, Uel, and the Spencer boys next time you write, and I will try and look them up. You would not know Wil and I now, we both have moustaches, and I weigh 70 kilogrammes, which is equivalent to about 11 stone, so you see I have put on a considerable amount of flesh already since leaving Australia. I have not received any papers from home yet, but got two letters from you.

We are now camped away out in the desert, surrounded by sand and myriads of flies, but we don’t do much work, and I am perfectly satisfied with the camp and quite contented. There is nothing here to worry about except news, and we don’t get much of that. We had about 100 mules to look after for about a week, and it was great sport watching some of the lads trying to stick them. There were a good many of them who did not have much of a grip of how to ride, but usually had a better grip of the sand. We have not many horses now, and no mules, and I am glad they are gone, for although they are wonderful pullers I have no time for them; they seem silly animals, and they can kick a fellow from any angle of the compass. Why I’ve seen mules kick mosquitoes off their ears without ducking their heads. “I love those mules and donkeys, but give me a horse.” There are any amount of camels about here, and the other day about a thousand went past the camp; it took the “train” about an hour to pass. The railway trains over here have three classes. The lst is very comfortable and more elaborate than the 1st class of the western line. The carriages have no breaks on them; the engines are the only parts with breaks, and the trucks are all red the same as the carriages. One of our cooks is a brother of a J. Macnamara, of Dubbo. Remember me to all Wongarbon friends.

Click here to view this article on Trove: http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article137412087