Bernard COYTE

Per his military service record (regimental no. 4757), Bernard Coyte was born at Borenore, N.S.W. He gave his age as 21 years and 1 month, his marital status as single, and his occupation as farmer & labourer. His description on his medical was height 5 feet 11 inches tall, weight 11 stone, with a dark complexion, brown eyes, and black hair. His religious denomination was Roman Catholic. He claimed that he had no previous military service. He completed his medical on the 14th October 1915 at Orange, and was attested at Orange on the 14th October 1915.

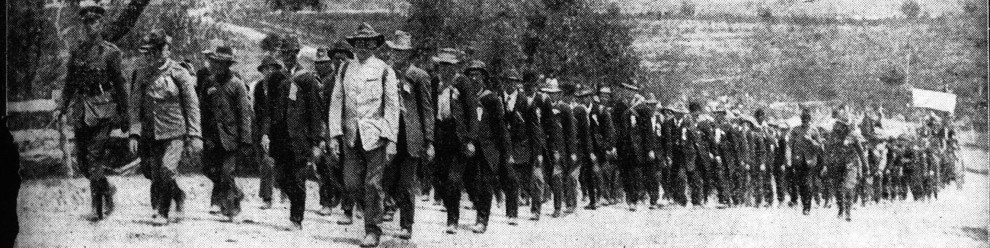

He was reported in The Leader on 22nd October 1915 (p. 6) as one of the men who had ‘volunteered to join in the Coo-ees march as recruits when they arrive in Orange’. His date of joining on his attestation paper in his service record was 23rd October 1915. He joined the Coo-ees when they arrived in Orange on Saturday 23rd October 1915.

After completing the march he went to Liverpool Camp as reinforcement for the 13th Battalion.

On his embarkation roll his address at time of enrolment was Borenore, near Orange, N.S.W N.S.W., and his next of kin is listed as father, W. Coyte, Borenore, near Orange, N.S.W.

On 8th March 1916 Private Coyte departed Sydney along with many of the other Coo-ees on the HMAT A15 Star of England, arriving in Egypt on 11th April 1916. He was immediately admitted to the 31st General Hospital at Port Said sick. On 3rd May 1916 he was transferred to the 1st Australian Dermatological Hospital at Abbussia. He was discharged on 8th June 1916. On 28th July 1916 Private Coyte was charged with being Absent Without Leave from 1700 to 1900 on 28th July 1916 at Tel-El-Kebir. He was awarded 24 hours Field Punishment Number Two.

On 6th August 1916 Private Coyte left Alexandria aboard RMS Megantic bound for England. After arriving in England, later in August 1916 Private Coyte was posted to the 4th Training Battalion. On 30th August 1916 he was charged with Being Absent Without Leave from 0900 to 1600 on 29th August 1916. He was awarded Three days confined to Camp and forfeit One days pay.

On 22nd September 1916 Private Coyte embarked for France. On 24th September 1916 he marched into the 4th Australian Division Base Depot at Etaples. On 4th October 1916 Private Coyte was taken on strength of the 13th Battalion whilst they were in action in the vicinity of Voormezele in Belgium.

On 15th January 1917 Private Coyte was admitted to the Corps Rest Station with scabies. On 23rd January 1917 he was transferred to the ANZAC R.B. sick with an illness Not yet Diagnosed. On 28th January 1917 he was transferred to the SMD Casualty Clearance Station sick.

On the 6th March 1917 he was discharged from Hospital to the 4th Australian Division Base Depot. On the 20th March 1917 Private Coyte rejoined the 13th Battalion.

On the 21st March 1917 Private Coyte was sent to the 13th Australian Field Ambulance with Influenza. On the 29th March 1916 he was admitted to the 3rd Australian Casualty Clearing Station with an Auxillary Abscess. On the 21st of April 1917 Private Coyte was embarked aboard the Hospital Ship St George for England suffering a Slight Debility. On 23rd April 1917 he was admitted to the Lewisham Military Hospital, and then on 30th April 1917 he was transferred to the Bermondsey Ladywell Hospital. On 28th May 1917 he was transferred to the 3rd Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Dartford, England. On 1st June 1917 he was discharged from 3rd Australian Auxiliary Hospital, and went on leave.

On 11th September 1917 he moved out of No. 1 Command Depot at Pernham Downs to Overseas Training Brigade at Longbridge.

On 2nd November 1917 Private Coyte departed Southampton for France. On 3rd November 1917 he reported to the 4th Australian Division Base Depot at Havre. On 13th November 1917 he rejoined the 13th Battalion when it was conducting training at Fontaine Lez Boulans, France.

On 14th January 1918 Private Coyte was charged with Leaving a Train Without Permission from 12 noon on 11/01/18 to 8.30 pm on 12/01/18 he was awarded 10 days Field Punishment Number Two and forfeit 12 days pay.

On 4th March 1918 Private Coyte was admitted to the 13th Australian Field Ambulance then to the 2nd Australian Casualty Clearance Station with a condition Not Yet Diagnosed. On 6th March 1918 he was transferred to the 19th Ambulance Train, then on 9th March 1918 to the 39th General Hospital. On 12th March 1918 he was discharged, and marched into the 4th Australian Division Base Depot. On 14th March 1918 Private Coyte rejoined the 13th Battalion whilst it was training at Neuve Eglise, France.

On 28th June 1918 Private Coyte went on leave to Paris. He returned to his unit on 11th July 1918.

On 29th July 1918 he was admitted to the 4th Australian Field Ambulance sick. On 30th July 1918 he was transferred to the 12th Casualty Clearance Station sick. On 10th August 1918 he was sent to the Australian Corps Rest Centre and on 18th August 1918 he rejoined the 13th Battalion whilst it was engaged in action in the vicinity of Harbonnieres, France.

On 18th September 1918 Private Coyte was killed in action during an attack launched by the 13th Battalion on the German Lines south of the village of Le Verguier, France. He is buried at the nearby Jeancourt Communal Cemetery Extension, France.

Private B. Coyte’s headstone at Jeancourt Communal Cemetery Extension, France (Photograph: S & H Thompson, 6/9/2014)

Private Coyte’s’s name is commemorated on panel 68 on the Australian War Memorial First World War Roll of Honour.

Private Coyte’s name is also listed on Borenore District War Memorial, and Orange War Memorial.